Nuria Rodríguez

Atlas Naturae: White Island

Story no. 1

In 1769, the explorer James Cook discovered an almost circular island with an active volcano in the South Pacific. The only visible mountain was a conglomerate of igneous rock, andesite. Its other name, Whakaari, is Maori for “the dramatic volcano”, but Cook preferred White Island because of the visible exhalation from the inside of the Earth; the clouds that formed in its centre constantly shrouding the relief of the island.

Coordinates: 37°31’23.2”S 177°10’57.1”E

—

Nature is still a mystery for the human species. We might know its rhythms and its functioning but unpredictable randomness is an element we can never manage to trap despite the attempts undertaken by our technological being which has made us believe in the possibility of a Homo Deus.

—

Story no. 2

In 1539, Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz was appointed lord and governor of Terra Australis Incognita, a continent imagined by Aristoteles and which Ptolomy represented as a large extension of land around the South Pole much larger than Antarctica, situating its limits a little bit further north. James Cook debunked the myth of this legendary continent and erased it from his maps and instead drew White Island where Terra Incognita was once thought to be.

Coordinates: an undetermined place in the Antarctic ocean (without coordinates).

—

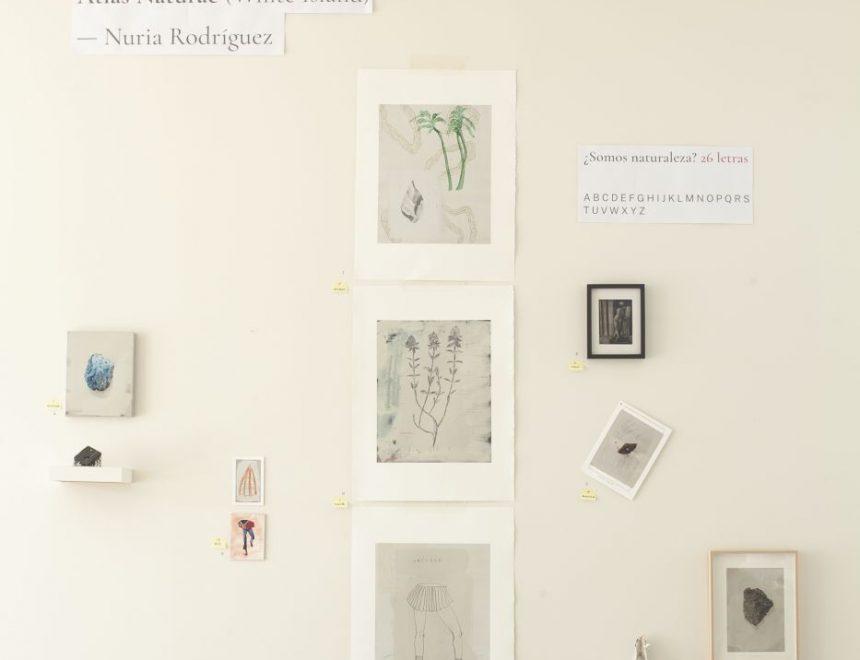

Atlas Naturae: White Island is an artistic intervention made specifically for the hall/workshop at IVAM Alcoi thanks to the IVAM Produces programme to support artistic production. The title of the project proposes a double play; first of all, it creates a visual atlas of nature, and for this purpose it engages with the work of the botanist Cavanilles which is then connected with James Cook’s voyage to White Island, generating a taxonomy of discoveries in images and words. Secondly, the installational mise en scène of the paintings, drawings, objects and videos identifies the analogue world with naturalia and the digital world with artificialia.

—

The dialogue we strike with our natural environment is wide-ranging and diverse. We have been able to date the creation of the Earth to around 4550 million years ago and also to visualize the Big Bang theory in a laboratory. We have studied the reproduction of bacteria in order to understand the beginning of the first life form and we have chronicled the voyage of Homo Sapiens through the Mediterranean, southern Europe and Asia since over 50,000 years ago through the remains we have discovered, while the other extension of ourselves travelled towards the confines of Ptolomy. Our memory is a memory of fragments, a mix of stories told by firelight. We have sculpted Demeter and painted Saturn devouring his children. At the same time, we have decoded the DNA sequence that recognizes Darwin’s theories on the evolution of the species and, now, we can watch online, as a result of our reckless ambition, as tonnes of ice melt into the sea from the coldest place on the planet, the land close to White Island and the imagined Terra Incognita.

—

My previous project, called Sistema Humboldt. Pensar/Pintar, proposed a random network of relationships between the University of Valencia’s Natural History collections, the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and the artistic production derived from this encounter through a glossary of paired words that opposed the world of intuitive randomness with the digital world of algorithms, the place where bodies disappear behind the liquid screen. However, the times of nature are different, and Atlas Naturae: White Island posits a new taxonomy, a tree of categories in order to reflect on what Humboldt defined as “that inextricable network of organisms by turns developed and destroyed—each step that we make in the more intimate knowledge of nature leads to the entrance of new labyrinths”.